In March, I dreamed I went to Hasankeyf.

It was one of those vivid dreams that seem like prophecies, dreams that don’t reflect what has happened, but what will be.

I pay attention to my dreams. I would go to Hasankeyf, and I would go soon.

Because soon, I wouldn’t be able to.

I knew little about Hasankeyf, Turkey before it invaded my dreams. I knew it was endangered. I knew that a group of expats and artists were passionate about saving it. I learned it was extraordinary when I finally visited in July, as part of my Trapped In Turkey Tour.

Hasankeyf is a tiny thousands-years-old town in the southeast of Turkey with a big problem. As part of the Southeastern Anatolia Project (also known as GAP), the Ilisu Hydroelectric Dam on the Tigris River will flood Hasankeyf, wiping out the town and dispersing the population. That would be tragic under any circumstances, but here it is particularly galling, because Hasankeyf is an extraordinary place.

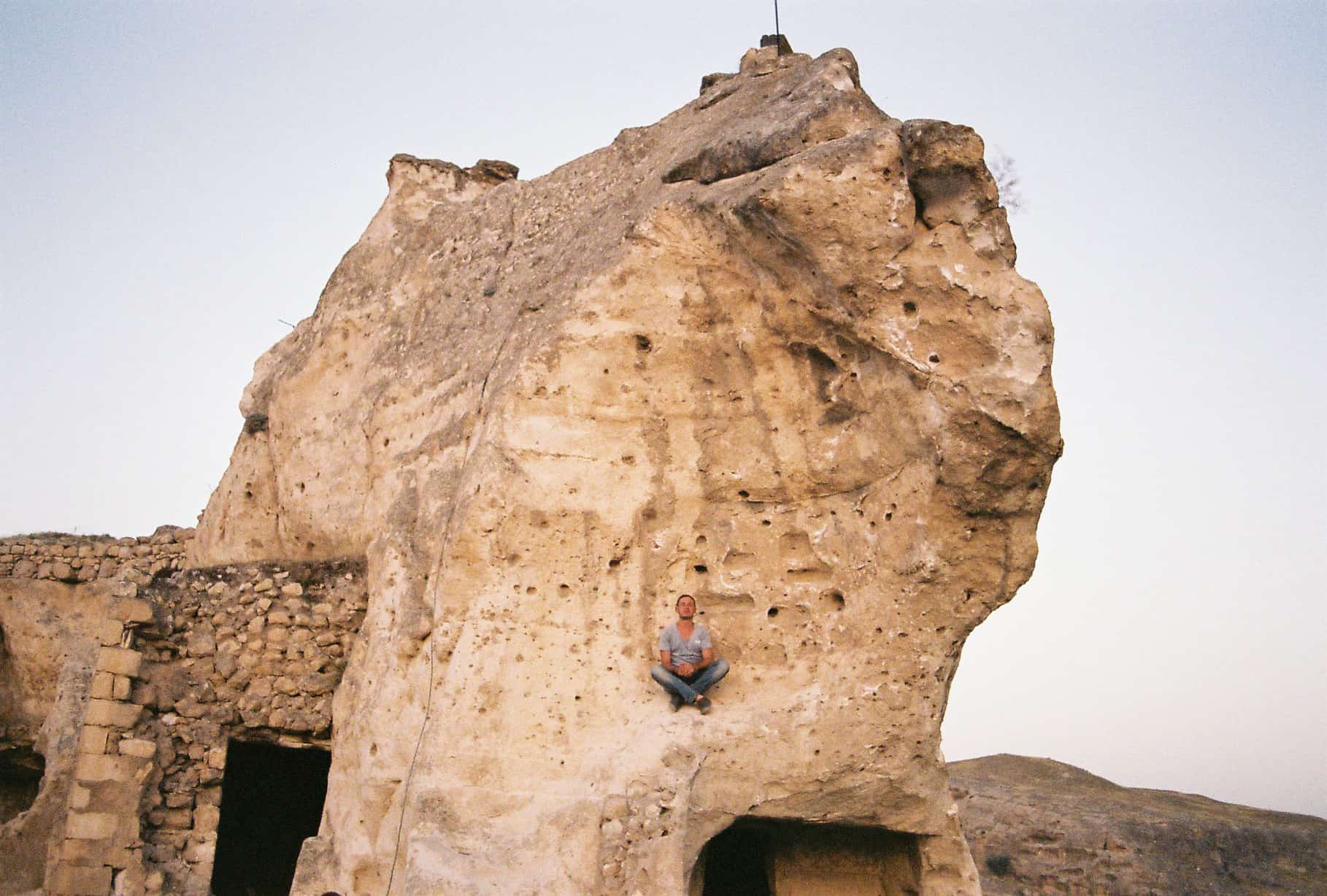

It’s an archeological wonderland, with structures reaching back to Byzantine times and across many architectural styles, including a Central Asian-style tomb, the Zeynel Bey Turbesi.

It’s naturally breathtaking, with rushing brooks, golden mountains, arid plains, and the mighty Tigris River. It contains a distinct cultural community. A UNESCO World Heritage site distinction would help save Hasankeyf, but only the Turkish government can nominate a site for the honor. With their determination to flood the river, it’s unlikely they would work against their own interests to preserve Hasankeyf.

It’s naturally breathtaking, with rushing brooks, golden mountains, arid plains, and the mighty Tigris River. It contains a distinct cultural community. A UNESCO World Heritage site distinction would help save Hasankeyf, but only the Turkish government can nominate a site for the honor. With their determination to flood the river, it’s unlikely they would work against their own interests to preserve Hasankeyf.

There are rumors that the dam won’t open. Many point to the preservation work that’s ongoing in Hasankeyf as proof—why put money into preserving something that will soon be under water? Yet there are new, shiny, ugly condos being built on the hills high above Hasankeyf, and they are ominously advertised as waterfront property. The residents of Hasankeyf cannot afford these condos, even with the payout they receive from the government. The community, instead of relocating whole, will be disbanded and spread out across Turkey.

And this is a problem in itself– it would be a true shame to lose not only the town but also the distinct community that lives in Hasankeyf. The people in Hasankeyf are often tri-lingual. Upon arriving, I assumed that our new friends were speaking Kurdish, since I couldn’t understand them at all (and therefore knew that they weren’t speaking Turkish). But I was wrong: like many people in Hasankeyf, they speak a version of Arabic that is specific to Hasankeyf. (I learned that there are five communities in Turkey with Arabic-speaking populations: Hasankeyf, Urfa, Mardin, Midyat, and Diyarbakir. It’s most apparent in Hasankeyf, because it is so small and relatively isolated.) If this community is dispersed, their dialect of Arabic and their distinct culture will be broken apart. The death of Hasankeyf is not just the end of a city, it’s the end of a culture.

I was lucky to meet John Crofoot, the only expat in Hasankeyf and a main force behind Hasankeyf Matters, the website dedicated to saving the city. John runs art workshops with the children of Hasankeyf, and he explained that Hasankeyf is “a depressed and traumatized community,” and the children’s drawings contain recurring images of rivers and mountains. They are growing up under the axe; their home will someday, possibly, simply cease to exist. He explained further how Hasankeyf has a problem marketing itself. Though it is home to amazing historic structures, there is no real iconic image of Hasankeyf; the ruins of its 12th century bridge comes closest, but are much more impressive in person. Unlike Mt. Nemrut, Pamukkale, or Cappadocia—all tourist attractions in Turkey that can trade on their famous images—Hasankeyf isn’t so easily summed up in one image. And yet, having been to all of these places, I would argue that Hasankeyf might be the more singular experience. In Hasankeyf, the draw is the lifestyle.

It’s less because of the activities available than because of the feel of the place. Hasankeyf seems set apart from time, removed from rush. My trip there coincided with the beginning of Ramadan (the Muslim month of fasting) and with temperatures that cracked 106°, which meant that days were slow, evenings were golden, and fast-breaking at dusk was exuberant.

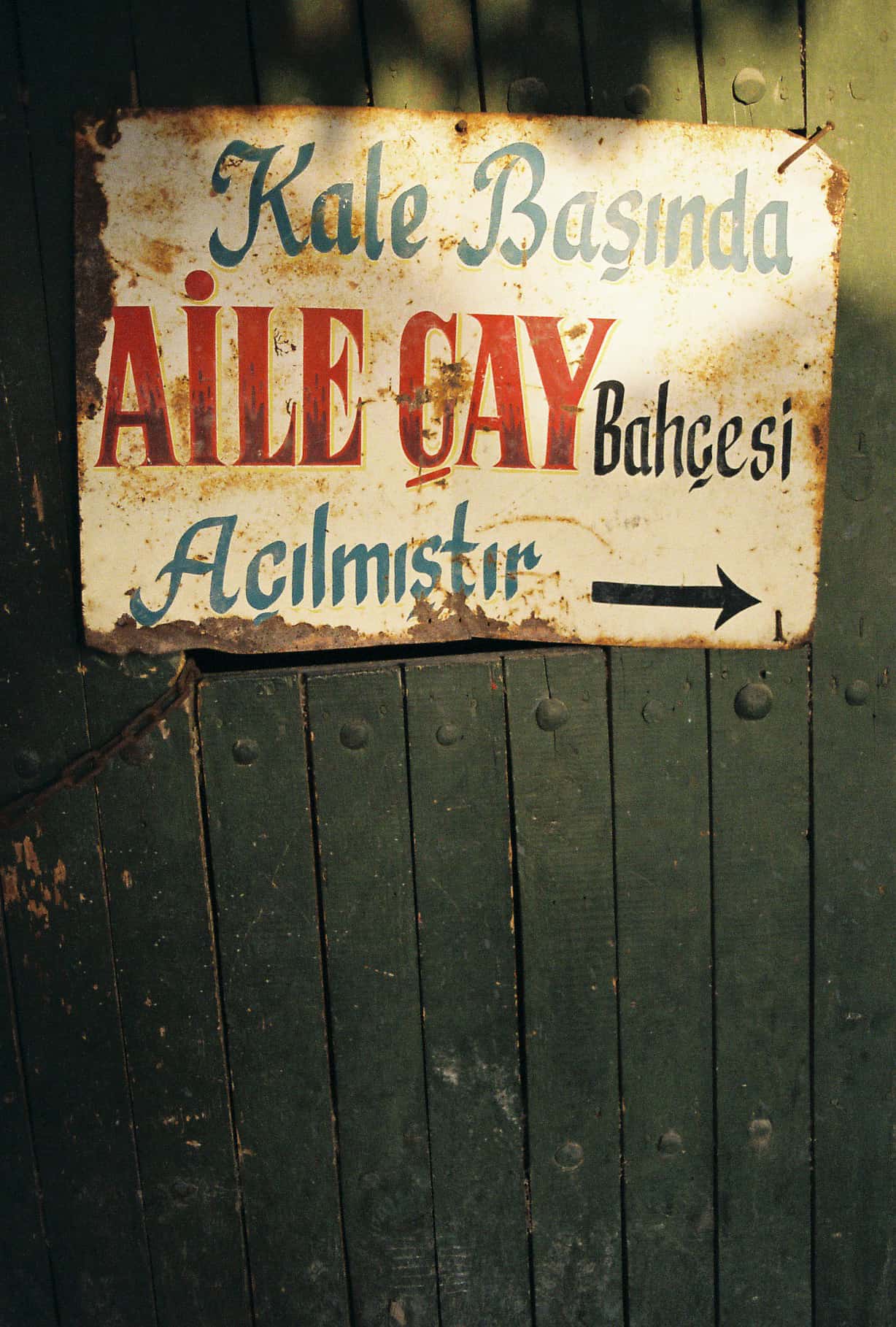

I spent long hot days in the hammock at the Hasbahce guesthouse, moving as little as possible and shooing away families of ducks and cats with torn ears. I wandered dusty quiet streets lined with men who have known each other their whole lives selling trinkets to a trickle of tourists. I partook in the iftar (fast-breaking) feast while watching a truly terrible Titanic sequel on Turkish television. I spent late nights under the stars on carpeted platforms perched above the Tigris River, eating fatty kebab and drinking cay and surrounded by the sound of buzzing bugs, the soft drone of the World Cup broadcast, and the laughter of men who have finally broken their daily fast.

I spent long hot days in the hammock at the Hasbahce guesthouse, moving as little as possible and shooing away families of ducks and cats with torn ears. I wandered dusty quiet streets lined with men who have known each other their whole lives selling trinkets to a trickle of tourists. I partook in the iftar (fast-breaking) feast while watching a truly terrible Titanic sequel on Turkish television. I spent late nights under the stars on carpeted platforms perched above the Tigris River, eating fatty kebab and drinking cay and surrounded by the sound of buzzing bugs, the soft drone of the World Cup broadcast, and the laughter of men who have finally broken their daily fast.

The people make the place– what hospitality! The kindness and fast friendship that I found in Hasankeyf led to adventures I couldn’t have had otherwise. My friends and I were treated to a golden hour hike and secret feast of watermelon cooled in a freshwater stream, local cheese, and pide bread– all before sundown on the first day of Ramadan, when every restaurant was closed.

The mountains vibrated with warm light, making every twist and turn in the path look miraculous. I became acquainted with Hasankeyf from above, reveling in its beauty.

The mountains vibrated with warm light, making every twist and turn in the path look miraculous. I became acquainted with Hasankeyf from above, reveling in its beauty.

We went swimming and splashing in the cold currents of the Tigris River, secluded except for a local shepherd napping in the shade. I felt uncomfortable wearing a bathing suit in this conservative part of the country, so I rolled up my pants and waded in.

It’s a strange feeling to realize you’re in the famous Tigris River, splashing near structures that are thousands of years old, and that the people in the community have grown up with this wonder as their playground.

It’s a strange feeling to realize you’re in the famous Tigris River, splashing near structures that are thousands of years old, and that the people in the community have grown up with this wonder as their playground.

And the most glorious– our friends acquired the key for the closed-off Hasankeyf Castle by sweet-talking the key-keeper; we climbed up in the darkness before dawn and watched the sun spill golden over the cliffs and ancient bridges of Hasankeyf.

Ascending to the castle used to require less stealth, but the future destruction of Hasankeyf has drained away much of the tourism. We passed hushed remnants of restaurants that have been abandoned in anticipation of the town’s imminent demise. “This used to be a very popular place,” our friend told us wistfully. Hasankeyf is a town dependent on its tourism, but its location deep in the southeast of Turkey (not so far from Syria or Iraq) and its future inundation have decimated the flow of visitors. A view of Hasankeyf at sunrise should have been bustling, open, popular. Instead, we snuck in during the gray morning light, and had the sunrise all to ourselves. Hasankeyf sparkled at the new day— it’s easy to forget that this beautiful place will be gone; remembering made me angry all over again.

In Hasankeyf, we lived in the golden hours: the splashiness of sunrise, the glowing of dusk. Something about the mountains and the water capture light in exquisite golden pools, land that looks barren and grim in the midday heat sparkle as the sun starts to sink. In the evening hours, the lethargy of the fasting day starts to turn into an anticipatory loopiness, which propelled us up mountains and down streams.

Describing a place as magical might be a cliché, but it’s the most appropriate way to explain Hasankeyf. Maybe it’s the way light and sounds echoes across the cliffs. Maybe it’s the radiating kindness of a downtrodden community. Maybe it’s just the slight breeze one feels when swinging gently in a hammock under pomegranate trees. Whatever it is– it is magical.

Now is the time. Go to Hasankeyf, quick—before Hasankeyf goes.

(To get to Hasankeyf, fly into Batman and take a short minibus ride to Hasankeyf. For more information about Hasankeyf and the attempts to save it, visit Hasankeyf Matters or like them on Facebook here. Also, from October 24-27, there is an Artists Ingathering in Hasankeyf—if you are free and in Turkey during that weekend, I highly recommend visiting then. If I wasn’t out of the country that weekend, I would be there.)

9 Comments

Natalie

October 5, 2014 at 9:37 AMAt what cost should development proceed. This is not the only area that is under threat. It is happening everywhere. The Turkish government has sold their soul to the devil

Katrinka

October 15, 2014 at 10:10 AMIt’s very sad.

Lauren Bassart

October 14, 2014 at 7:19 PMI hate seeing development taking over nature. I understand that we need places to live, but at what cost.

Katrinka

October 15, 2014 at 10:09 AMYes, it seems like a true shame to completely wipe out this town!

Helen Anne Travis

October 14, 2014 at 7:52 PMWow, I’ve never heard of Hasankeyf before. Thank you for sharing this!

Katrinka

October 15, 2014 at 10:10 AMYou’re welcome! More people need to hear about it; Hasankeyf is really a wonder.

Jenna

October 15, 2014 at 10:28 AMWow–what a beautiful community–I would love to visit! It’s so sad that it is facing destruction. I hate seeing things like this happen due to development. 🙁

Corinne

October 18, 2014 at 11:20 AMKatrinka, I loved Hasankeyf and it just makes me want to cry to think it will soon be long gone. I hope people take your advice and go!

rabirius

October 25, 2014 at 2:22 PMHasankeyf is such a beautiful place – and I’m really sad to see it go.

I already visited it 3 times and know a lot of people there – and learned a lot about what the construction of the dam will mean for them.

I already posted a lot about Hasankeyf and I’m also grateful for everybody who spreads the world that this beautiful – and from a historical point of view – very important place will be destroyed soon.

Greetings,

rabirius.