Two years ago, soon after I’d returned from a reporting trip in Tunisia, I went to a party on a roof during a hazy hot Istanbul night, and I met a lovely man. By the time I left for a visit to the US two weeks later, we were involved. He took me to the airport and over my twelve-day trip, he wrote me letters and sent me Spotify playlists full of Rachmaninov. I sent him pictures from my travels: my best friend twirling in her wedding dress on a lush New England lawn, my sister in our parents’ backyard, me snapping a photo on Boston’s Longfellow Bridge.

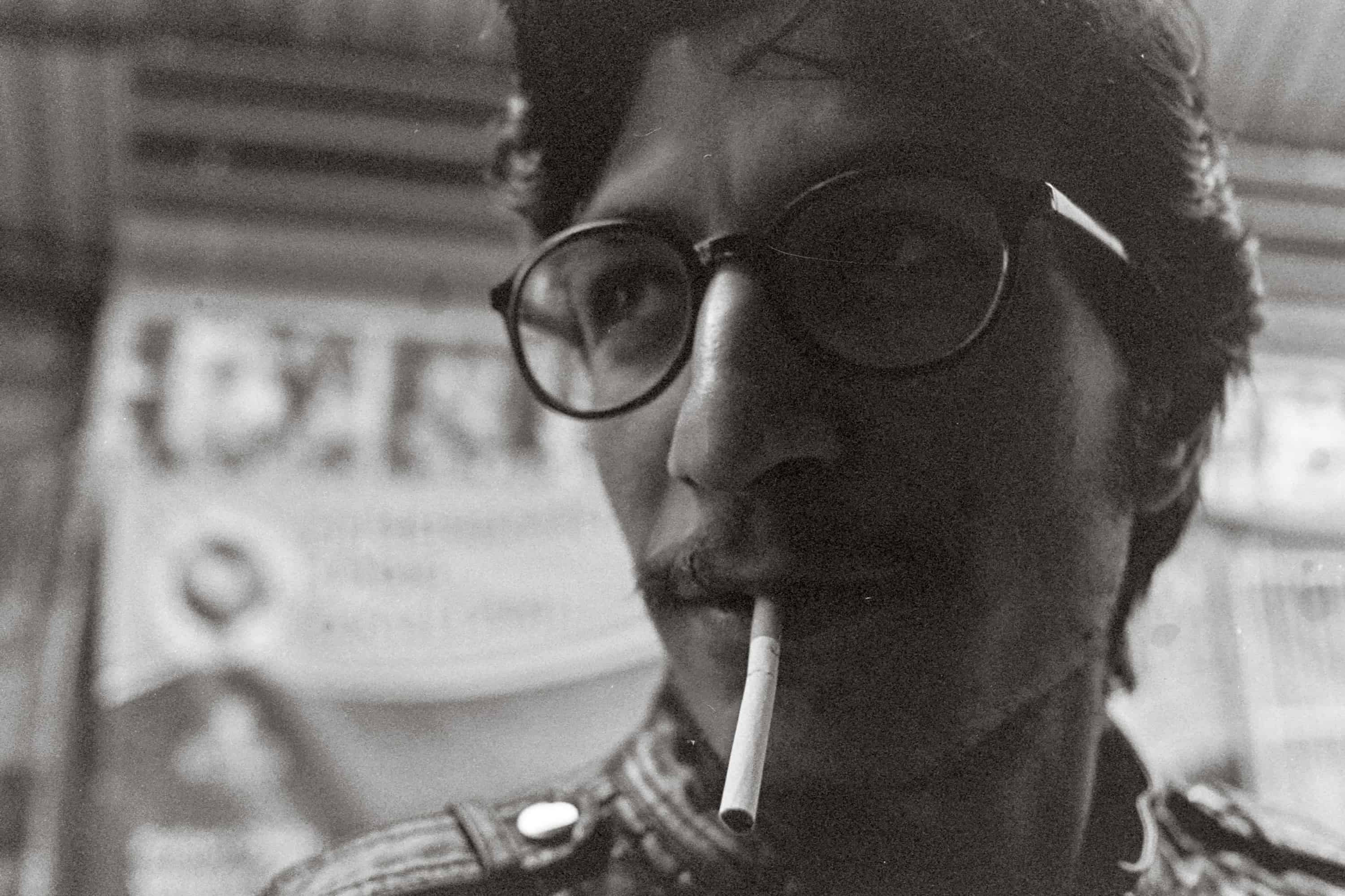

I think all of that sounds fairly normal— of course two people who have just started dating and find themselves temporarily in different countries will want to share their experiences. But for us, the situation was a bit more surreal, because I was a writer who often writes about travel, and my new paramour was an Iranian refugee without a passport. In the first three months of our relationship, I was gone for weeks, traveling through Massachusetts and California and all over Albania from north to south. He stayed in Turkey, the only place he ever had been besides Iran, the only place he had been in the last five years.

“Is it okay if I talk to you about my trips?” I asked him early on. Often, my life can feel like a series of travel plans, with months reshaping around my plane tickets and itineraries. I didn’t want to be insensitive or gloating with this sweet man, but I wanted to talk to him about my life.

“No no canım!” He grinned. “I love hearing about your travels. Please tell me everything.”

And over the last two years— through the beginning and end of our relationship, and onward through our glorious and continuing friendship— I have told him and shown him as much as I can, to nurture his curious mind, to share the things I experience. This gentle man, who spends his spare time making educational science videos in Farsi and listening to philosophy podcasts, can’t go to the places I visit, but he can absorb as much as possible through my stories.

I guess that’s what travel writing is, on some basic level— a way to share the things that we experience, so those reading along can fill their minds with dreams and ideas and knowledge of many different parts of the world. But I am able to pursue this life and career by a quirk of luck: I was born white and well-off in the United States of America during a period of American dominance. Now, I am a writer during an age of migration and displacement, of accelerating globalization and growing xenophobia, and these days I’m not always sure how to write about travel when politicians demand that the borders be closed— to some. To the “illegals”, to “those people.” To people who did not inherit the quirk of luck that I did— an American passport.

Living in Turkey means that the reality of refugees and migration is inescapable, and as I travel with ease and often spontaneity on my American passport, I can’t help but think about how unfair it really is. I have too many friends who have limited international movement, whether because they have weaker passports or Syrian passports or no passports at all.

In 2018, 2275 refugees died in the Mediterranean Sea. Despite the fact that the Greek-Macedonian border (and therefore, the Balkan Route) was closed in 2016, despite the fact that the Dublin Regulation traps refugees in the first place they are registered (which is often and unwillingly a tiny Greek island), despite the fact that right-wing anti-immigrant politicians rise to power throughout Europe, people continue to make the dangerous crossing on tiny boats in the dead of night, in search of something like hope. The journey from Kuşadası, a port near Ephesus (an ancient Greek site dating back to the 10th century BCE, famous for the 2nd century AD Library of Celsus and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site) and the Greek island of Samos (famed as the birthplace of the mathematician Pythagoras and the fable-writer Aesop, visited for its splendid beaches) takes 90 minutes on a scenic ferry over the cerulean sea— if you have a “good” passport. Without, you must trust a smuggler to whom you’ve potentially paid thousands of euros, board a vessel that hopefully stays afloat, and navigate the inky water in the slippery night over molasses-slow hours.

Either way, the sea you are sailing over is a graveyard.

Both of these realities are happening simultaneously. By day, tourists still visit Samos, sip the local Muscat, swim offshore in sublime bliss. By night, the boats keep coming. The lucky ones live. The luckier ones get off the island. Many don’t: according to this article from EuroNews, the refugee camp on Samos is overwhelmed with more than 4000 people, way past the 650-person capacity it was built for. The paradise getaway is also a prison.

What makes my writing about places like Samos “travel writing,” and not the narratives of or about those seeking asylum? I think those are also travel stories, and relevant ones; the fact that the journey is easy for someone like me and treacherous for a refugee doesn’t change the fact that both are travel stories. I have felt a block for much of this year, reluctant to pitch and write these light travel pieces that don’t make room to deal with the reality that travel is sometimes the ultimate luxury, and other times the ultimate necessity.

So what is the proper thing to do? How can I write about travel without acknowledging the stress of traversing borders, the difficulty our governments are imposing on asylum seekers, the rage I feel every day?

The past leaves a legacy but we do too; we are sending out our modern-day Odysseuses to test their luck at sea, or stretch their fortune through the Sonoran Desert, or carry their children across the Rio Grande, or find a future through other unsafe paths. I still think it’s important to travel— god, now it’s more important than ever— for there’s no better way to learn about a place and love it with your adventurous heart, there’s no better way to subvert the stories you hear on the news and meet the real people who are living real, vivid lives. I don’t know if Americans get to meet refugees, because (shame of all shames) my country doesn’t let many in. But I wish they could.

Last autumn, my dear Iranian friend left Turkey on one of those boats crossing at night between Kuşadası and Samos. When he told me he was leaving, I sobbed; then I went out and bought him a life jacket.

“The first rule is: don’t die,” I said to him many times in the days before he left. “Promise me you won’t die.”

“I promise I won’t die, canım,” he’d say, and then laugh his big-hearted laugh.

The night his boat set out, he shut his phone off early around 6pm and I spent six hours at home in the dark, watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer, waiting to hear the news that my friend did not die.

Hours, hours, hours dragging along. Please don’t let him die.

12:40am, I received a WhatsApp message.

“Arrived”

“Safe”

Someone I care about traveled in a tiny boat from Turkey to Greece, in search of something like hope.

How can I ever write a fluffy travel piece about Ephesus or Samos again?

10 Comments

Nele

June 28, 2019 at 11:12 AMThanks for writing this! I don’t have an answer, but I think writing about this topic and drawing attention to it instead of looking away, as it is so easy to do, is already worth a lot!

Katrinka

July 1, 2019 at 10:52 AMI hope you’re right! Thank you for reading 🙂

Heather

June 29, 2019 at 12:26 PMBeautiful article, thanks for sharing.

Katrinka

July 1, 2019 at 10:52 AMThank you so much.

Madeleine

July 1, 2019 at 1:18 AMExactly that handsome man was reading your articel to my friend and me on a beautiful rooftop by night. It was … no words can describe that moment. Thank you!

Katrinka

July 1, 2019 at 10:51 AMAh yes he told me about that! I’m so glad it touched you and I’m glad you get to spend time with sweet B, he’s one of my all-time favorite people <3

ML

July 19, 2019 at 6:41 AMGreat article. More people need to think about these issues.

Jo

September 14, 2019 at 10:12 PMBeautiful and sad post…..it is a sad part of the world we live in with nationalism rearing it’s ugly head again. Travel and accepting refugees into our countries only helps to break down the barriers between cultures and spreads understanding. Keep writing your travel stories.

I am fortunate to have been born in New Zealand where we can have two passports. On my latest application for an ESTA (visa waiver) US now wants to know if we have more than one passport and which social media sites we follow. My reaction was to wonder how this would impact on entry as it is a new requirement. Your post puts into perspective any worries about that!

My grandmother and family came to NZ in 1877 from Ireland. A year later her sister married the ships Captain, and they sailed back to England…..never to be heard from again. The ship went down north of Australia near Indonesia. When I hear about the huge numbers drowned in the Mediterranean I feel so sad for their families who will never know what happened to their loved ones. I wonder how history will judge us.

I am now stuck on the question….what can we do?

Lucia

December 3, 2019 at 11:53 AMKatie, I have tears in my eyes reading your story. The story of sweet B, the story of hope, the story of differences…. It is so politicized, but in its essentials its human. we are all human beings, with feelings of anger, sadness, worry, fear, desperation, and despite of that there is also always joy, happiness, love, tenderness, trust, peace…. even in the most difficult circumstances we can access all these range of emotional experiences.

travelling for me also means to travel into other peoples minds, try to experience a glimpse of their reality, and feel the commonalities between us as human beings as well as learning from the differences. Thanks a lot for sharing your experience and letting us travel with you.

Katrinka

December 3, 2019 at 10:39 PMYou found it 🙂 Thank you for reading this piece and feeling it so fully!